Thinking About Sketching with Robert Henri

Thinking About Sketching,

with notes from American Painter Robert Henri from The Art Spirit, 1923

Some basic notes on Robert Henri: Born in June of 1865 in Cincinnati, Ohio, Robert Henri was a painter and art educator who worked and taught on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. He loved the Impressionist movement with its everyday subject matter and immediacy. Later, he evolved his point of view to find the Impressionists just another form of Academy. Henri wanted artistic representation to be instantaneous, fearless, rapid, and honest.

Henri taught art throughout his life as a means of income, and wrote The Art Spirit (or rather, his ideas and philosophies were compiled into it by Margery Ryerson, a former pupil). He was the founder of the ‘Ashcan School’, a movement of American painters who represented the dark, uncomfortable realism of city streets at the turn of the century in America.

Here are some notes I took from The Art Spirit on the subject of sketching.

The sketch hunter has delightful ways of drifting about among people, in and out of the city, going anywhere, everywhere, stopping as long as he likes - no need to reach any point, moving in any direction following the call of interests.

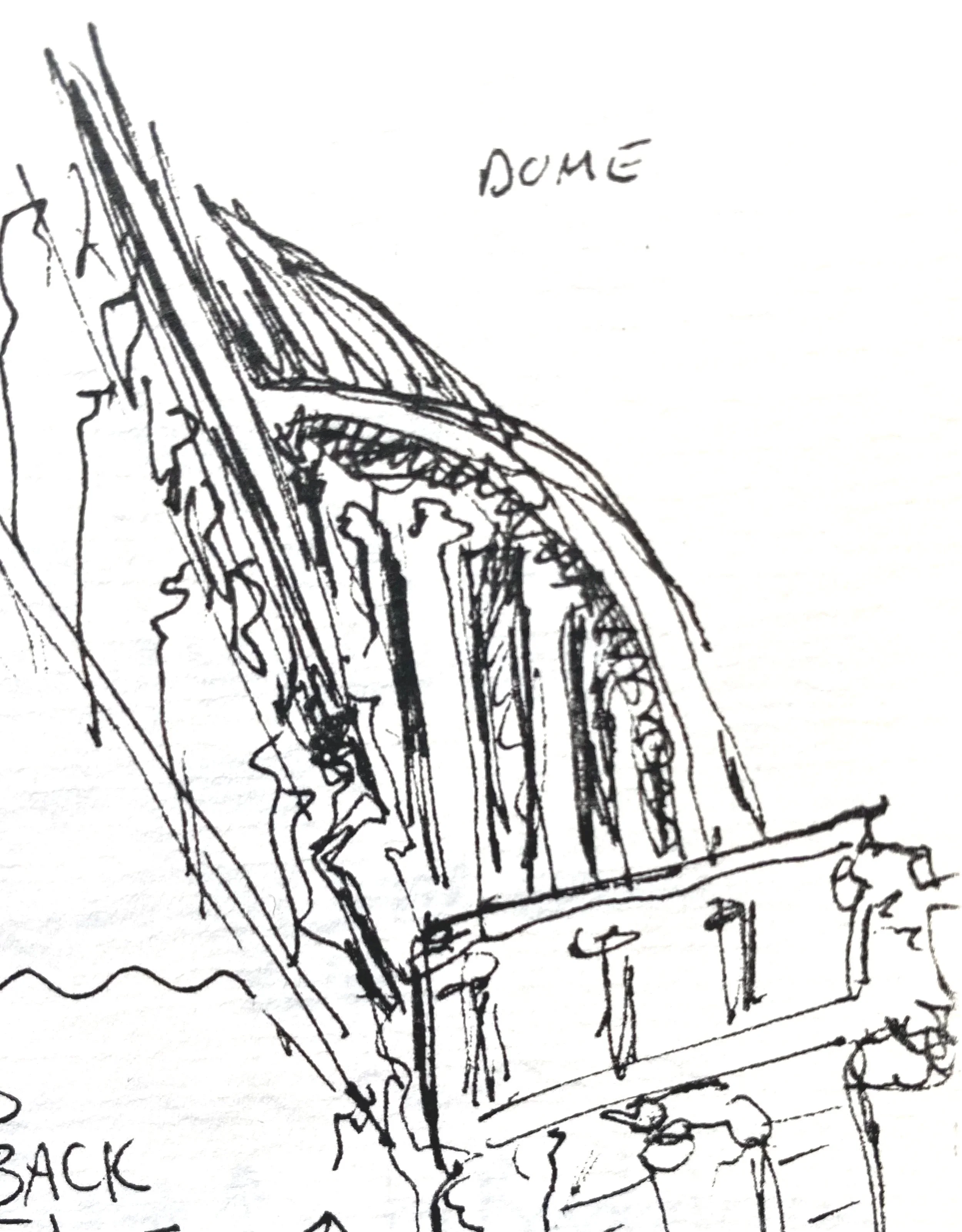

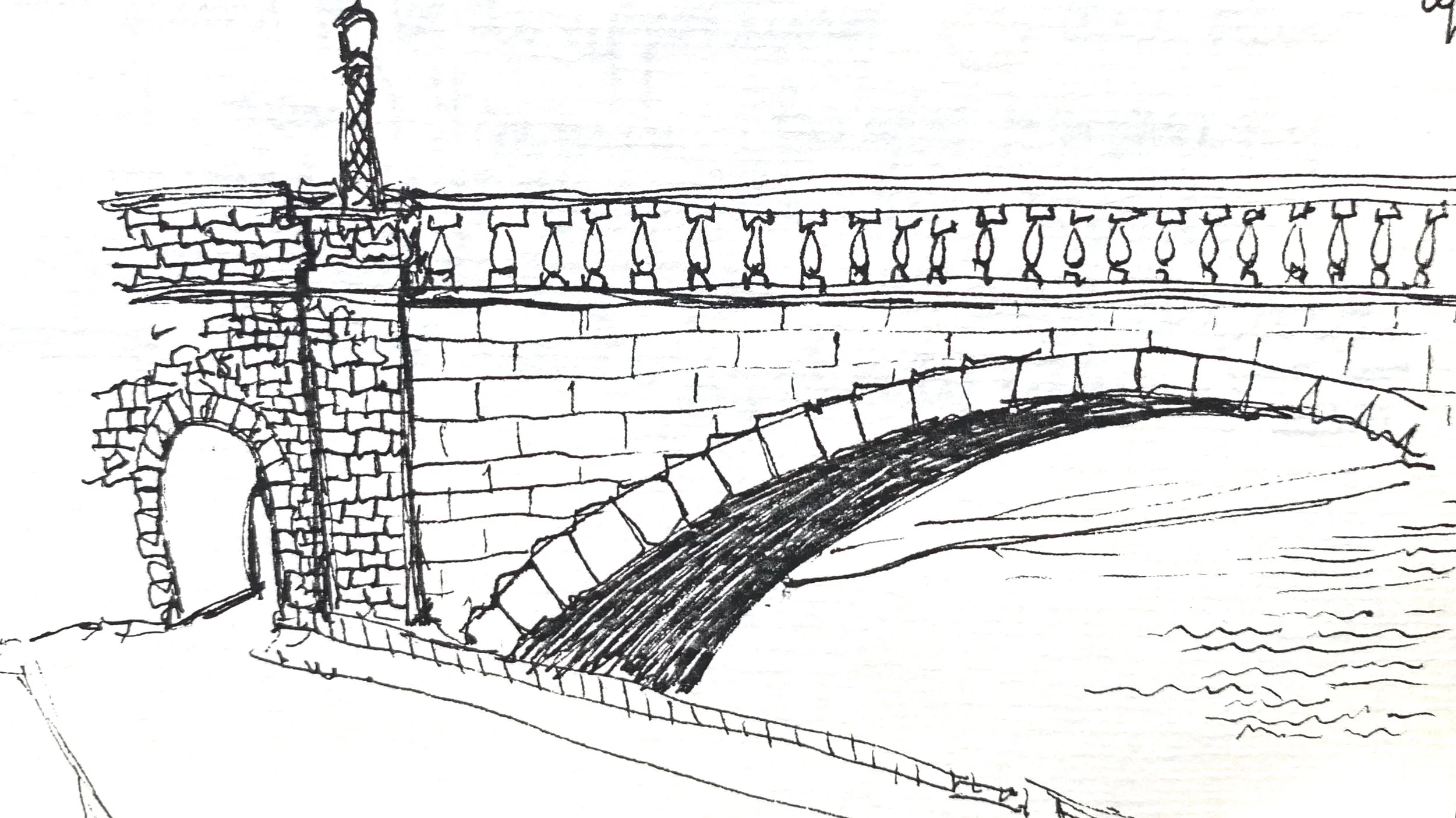

I recently had the opportunity to visit and sketch in Domme, France, followed by a week in the museums, galleries and restaurants in Paris. What an absolutely fabulous time. I wish I had stopped even more often to sketch corners of the city, but was too busy soaking it in. Most of my drawings happened inside the comfortable confines of a museum, I’m ashamed to say. Henri would be unhappy. For him, sketching in the bleakest slums was an important way to express human suffering in an almost journalistic way. His use of the location ‘city’ is important - this is not plein air work he is describing. It takes place on the sidewalk, surrounded by the ashcans after which his movement was named.

Henri describes the aspects of sketching which resemble hunting - or at least, collecting. There is an element of ownership when one captures a subject to one’s satisfaction. The subject is known more deeply as it now lives in the artist’s brain, hand, and sketchbook.

Henri describes the sketcher as a predator. He moves through life as he finds it, not passing negligently the things he loves but stopping to know them, and to note them down in the shorthand of his sketchbook, a box of oils with a few small panels, the fit of his pocket, or on his drawing pad. Like any hunter, he hits or misses. He is looking for what he loves, he tries to capture it. It’s found anywhere, everywhere. Those who are not hunters do not see these things. The hunter is learning to see and to understand - to enjoy.

Because the artist gets to choose when to stop in the city, what to see and focus on, it’s a personal process of becoming acquainted with something alien through the artistic process. As the sketch develops on the page or panel, no one else is involved in the process; no teacher offers pointers on composition, no buyer suggests a brighter colour. The sketch is meant to unfold for the pleasure, the skill development, the curiosity, and the instinct of the artist. Perhaps because of the privacy inherit in sketchbook work, this is the place where the best things happen. It’s a personal process, better without the scrutiny, oversight, time limits, pressure around production, end use, success, prettiness. Does this freedom from judgement lead to greater confidence in the sketching process? Does it enhance the artist’s pure, uncluttered perception of the subject without the distractions, interference and hesitation? And finally, again from Robert Henri:

There are memories of days of this sort, of wonderful driftings, in and out of the crowd, of seeing and thinking, where are the sketches that were made? Some of them are in dusty piles, some turned out to be so good they got frames, some became motives for big pictures, which were either better or worse than the sketches, but they, or rather the states of being and understands we had at the time of doing them all, are sifting through and leaving their impress on our whole work and life.

One’s interests lead you through the maze of offerings and subjects, intuition and affinities - it's a wonderful way of making sense of being a tourist, looking up a few shows or museums that fit your own taste and interests, look for a specific type of scene or element in the city streets of a strange country.

Although one is aware of the privacy violation of poking through an artist’s sketches or rough studies, they are compelling. Why are the sketchbooks of William Blake more vibrant, captivating and graphically appealing than his paintings? Where was that - the Met or the Tate where they had an entire gallery laying out his rough, quick work, and it was magnificent. Or the small oil sketch panels of Tom Thomson - so graphically pure and electrified with colour, they are like small jewelled rectangles on the gallery wall.

Does the luxury of time and space with more ‘finished’ work actually work against the process of seeing clearly and representing accurately? Henri might agree.