In Consideration of Rocks and John Berger

There is a great collection of essays by John Berger called About Looking from 1980.

You can read and reread these lovely, accessible musings on how and why we gaze at particular things.

One essay, “Courbet and the Jura” was originally written in 1978. In it there is an interesting passage about how Courbet integrates rock faces into his paintings.

Berger writes “Rocks are the primary configuration of this landscape. They bestow identity, allow focus.”

You can see why one would return to these essays over and over again - “Bestow identity, allow focus.” Pure gold - almost poetic language.

But wait a minute - aren’t we talking about just rocks. We study Rocks and Minerals in Ontario in grade 4, memorizing their types and how they were formed (igneous, metamorphic, sedimentary! Granite, limestone, quartz!). When we drive far enough north of highway 7, these amazing facets and monuments of rock break through the greenery at the sides of the road. No geological formation in the world is as taken for granted as the Canadian Shield. We see these incredible combinations of vertical and horizontal planes slicing through space, and we let our gaze slide over them as if it were nothing at all.

Back to Berger and his contemplation of Courbet.

“It is the outcrops of rock which create the presence of the landscape. Allow the term its full resonance, one can talk about rock faces (his emphasis). The rocks are the character, the spirit of the region. Proudhon, who came from the same area wrote ‘ I am pure Jurassic limestone’. Courbet, boastful as always, said that in his paintings “I can even make stones think.”

Berger continues, “A rock face is always there. (Think of the Louvre landscape which is called the Ten O’clock Road). It dominates and demands to be seen, yet its appearance, in both form and colour, changes according to light and weather.”

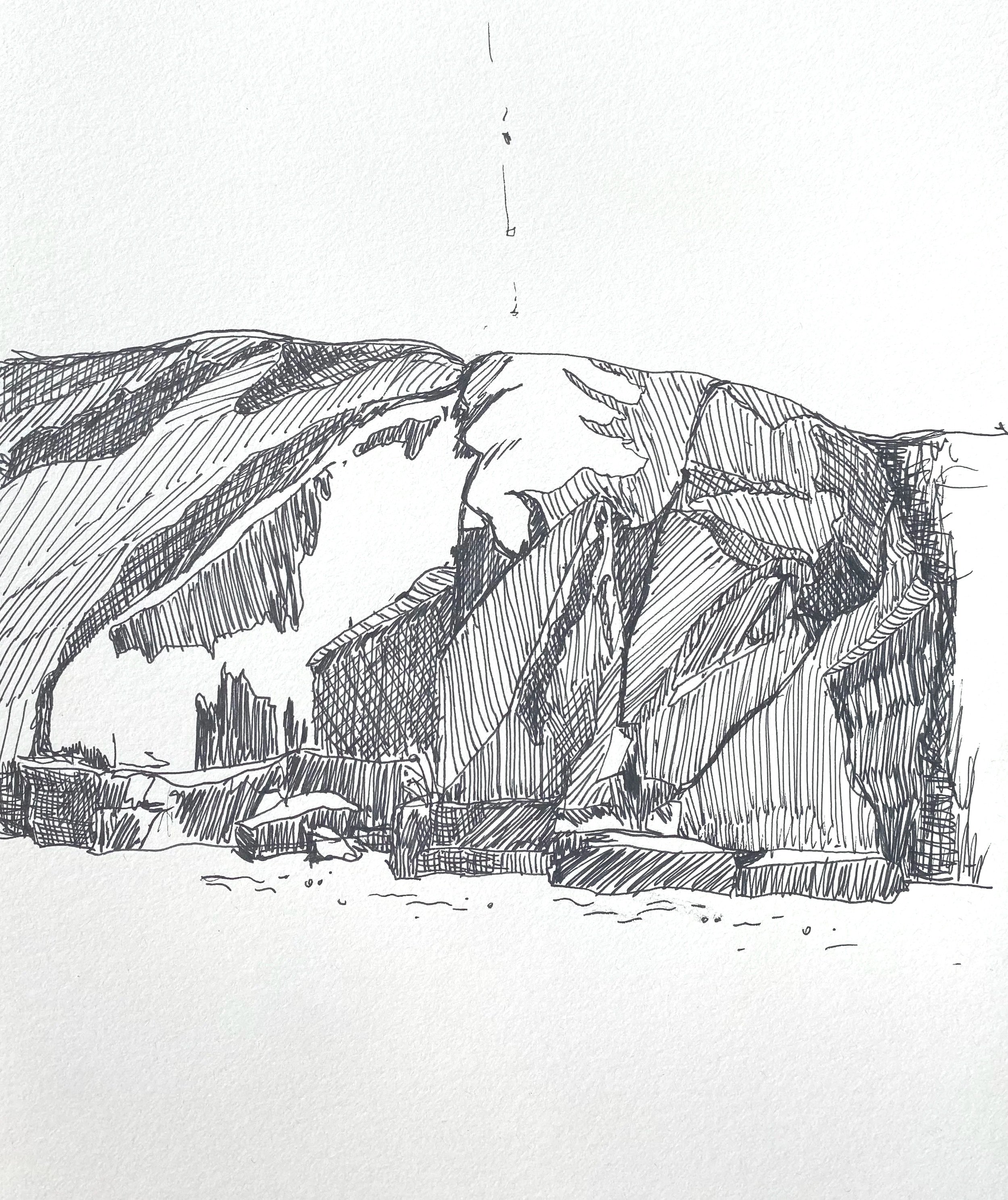

This is what attracts me to drawing natural stone and rock formations, where one can find such a place. Much of what we perceive to be a natural rock formation in the southern end of our fine province is actually a result of human intervention, blasting and carving through the natural rock deposits to make the road flatter or more accessible. A stream bed is the perfect place to see rocks carved and sculpted by natural forces, piled on themselves and falling over, never looking the same way twice.

And Berger again: “It (a rock face) continually offers different facets of itself to visibility. Compared to a tree, an animal, a person, its appearances are only very weakly normative. A rock can look like almost anything. It is undeniably itself, and yet its substance does not posit any particular form. It emphatically exists and yet its appearance (within a few very broad geological limitations) is arbitrary. It is only like it is, this time. Its appearance is, in fact, the limit of its meaning.”

Which means possibly that the representation of rocks in drawing or painting can offer great freedoms. Everyone knows what a tree is roughly meant to look like. But with rocks, the recording process is open - make all the mistakes you want, emphasize whatever you feel is important, shards, light, shadows, cracks, lichen, growths, boulders, and no one is the wiser. I’ve noticed lately when visiting a local waterfall, if the painting is feeling too forced, I can draw some rocks to loosen up and reconnect with the simple act of looking.

Finally, again from Berger, “To grow up surrounded by such rocks is to grow up in a region in which the visible is both lawless and irreduceably real. There is visual fact but a minimum of visual order. Courbet, according to his friend Francis Wey, was able to paint an object convincingly - say, a distant pile of cut wood - without knowing what it was.” (Berger, 1978)

This interesting tension between ‘visual fact but a minimum of visual order’ is appealing to me in the representation of rocks. We can stare at a mountainside in wonder, not even understanding the structure of the rock beneath and around us but still enjoying the wonder of it. The same kind of tension exists in cloudscapes, with the added emphasis of light and colour.